How to create sustainable communities

First published in ACES Terrier, Autumn 2022 edition.

Around 80% of local authorities in England and Wales have declared a climate emergency, but many face significant barriers as they try to implement the urgent action that is needed to reduce the impacts of the climate crisis and deliver net-zero carbon by 2050.

More than a decade of cuts to council budgets has reduced the resources available to planning authorities and put additional pressure on councils to achieve ‘best value’ when disposing of local assets. And national building regulations do not yet address the whole-life carbon emissions associated with new development, leaving ambitious, sustainability-driven developers locked-out of the market by high land values.

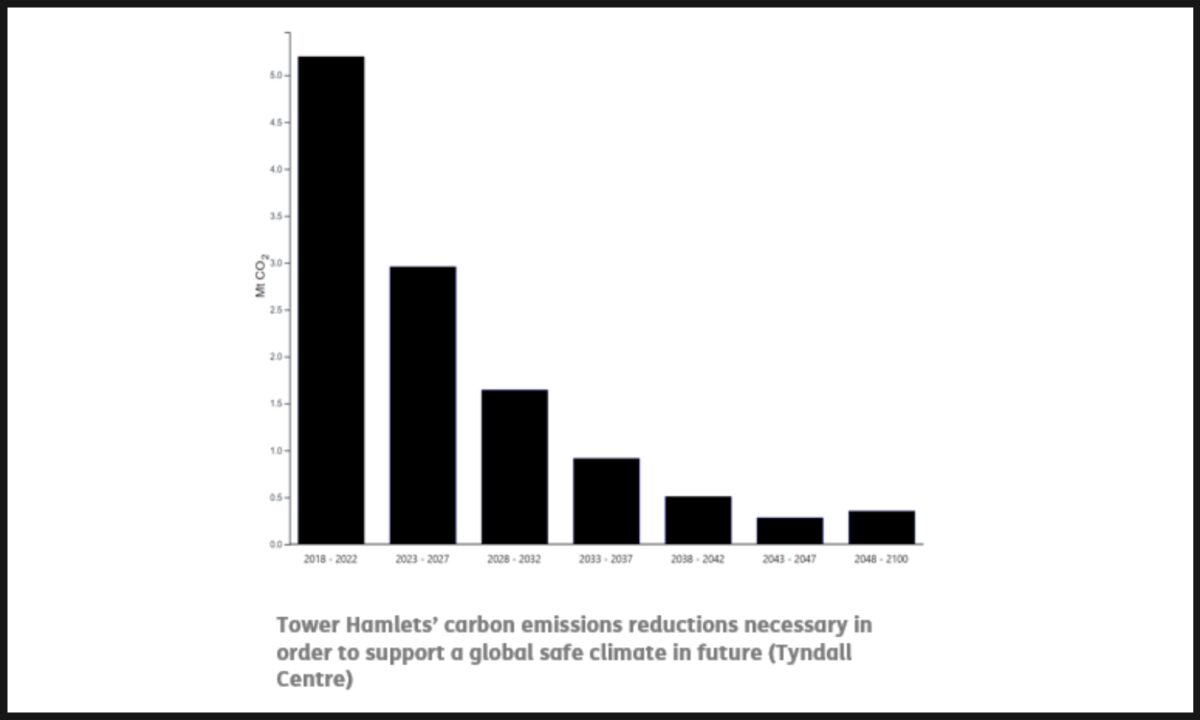

These barriers must be overcome - and quickly. While 2050 may seem far away, the decarbonisation trajectory we need, according to the latest climate science, requires we roughly halve direct emissions by 2030 - just eight years’ time.

However, there are significant opportunities for estates professionals. By working imaginatively with partners and looking beyond short-term financial considerations to take a holistic view of the impact of new development – ‘triple-bottom line accounting’ – local authorities can leverage their land and assets to create thriving, resilient, and sustainable communities, which bring with them wider financial benefits such as reduced spending on health, welfare, and environment.

But what do we mean by a sustainable community, and how can local authorities work with their partners and stakeholders to deliver them?

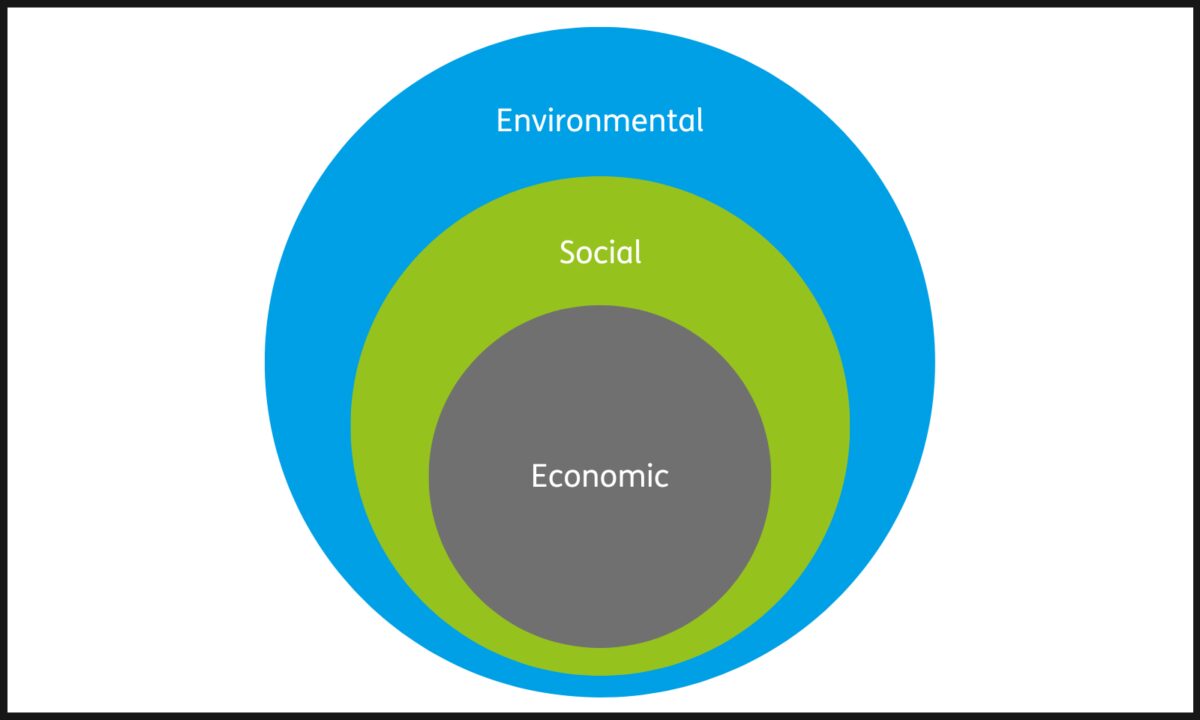

The traditional view of sustainability envisages three ‘pillars’ – environmental, social, and economic. This gives the false impression that each of these pillars are of equal importance.

A different model – of nested circles – gives a truer understanding of the relationship between these elements. Of course, our economic system is necessarily situated within, and dependent on, our society for its existence – economics is a social construct that does not exist without people. Likewise, society is necessarily situated within and dependent on the natural goods and services that are provided by the environment, and are essential for our survival.

This means that true sustainability will have environmental considerations at its heart. It follows that creating sustainable communities will generate tangible benefits – from the regeneration of natural ecosystems to the improved health and happiness of communities – that are not captured by the traditional and narrow assessments of short-term financial returns.

Government policy is moving slowly towards providing the necessary framework to encourage sustainable development, although in other areas, recent policy such as reversing the ban on fracking and opening up new oil and gas licences is clearly a step in the wrong direction. At a high level, the Climate Change Act 2008, as amended in 2019, places a legal duty on the government to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

The Environment Act 2021 contains several environmental protections and targets, most notably the requirement for new development to achieve 10% net gain in biodiversity.

The Social Value Act 2012 places a requirement on all public sector organisations to consider societal, environmental, and economic wellbeing in determining contracts, although there is complexity in how this applies to asset and land deals.

And the local economic agenda is, at present, being delivered through the levelling up white paper and Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill 2022. While not yet law, this contains proposals to ease the compulsory purchase order process and simplify the funding of local infrastructure through developer contributions.

These policies are necessary but insufficient.

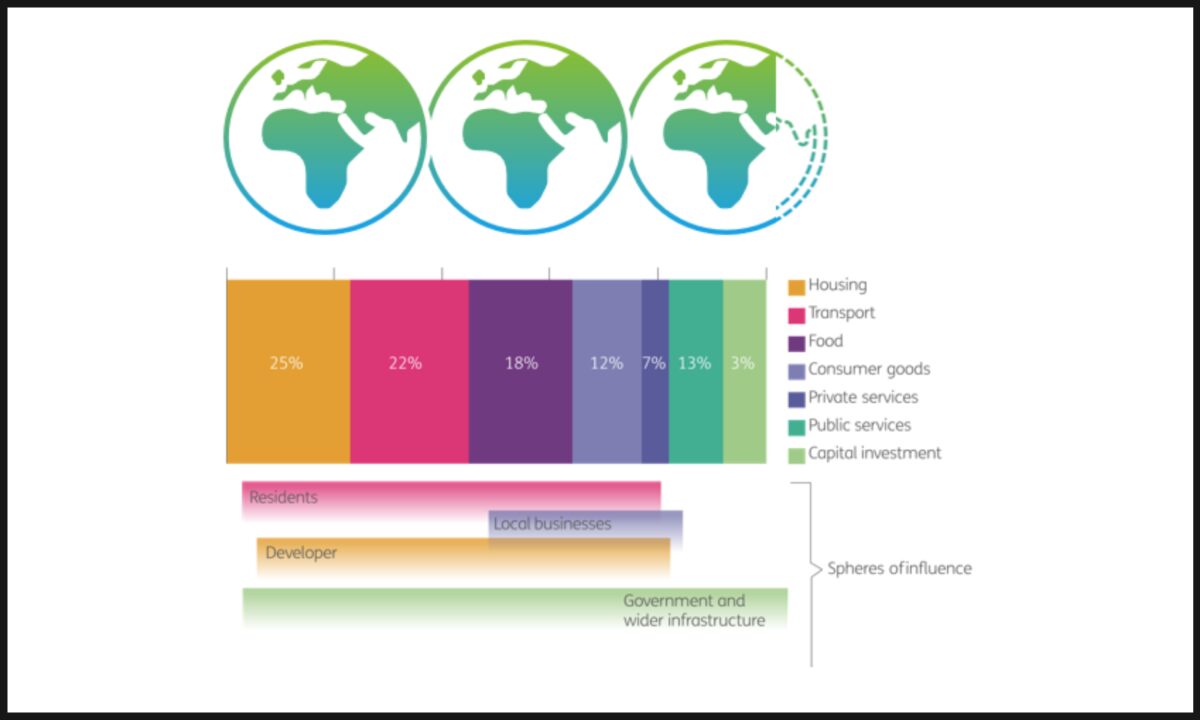

To live sustainably means living within our planetary boundaries. Our planetary impact arises from housing and transport, the food we eat, the goods we consume, and the services we use. If everyone in the world lived like we do in the UK, we would need almost three planets to support our lifestyles.

In response to this challenge, Bioregional created the One Planet Living framework in 2003. One Planet Living is a holistic framework consisting of 10 simple principles that cover the full range of social, economic, and environmental factors that need to go in to make a sustainable community.

Underpinning these principles are sector-specific goals and guidance, and a manual for how to implement them. One Planet Living has been used by communities, cities, and developers around the world. It has informed the creation of billions of dollars worth of real estate projects globally to date, with 1.3m people living or working in One Planet Living projects.

These principles provide a vantage point from which to envisage how new development can be genuinely sustainable.

Health and happiness Design climate-resilient homes and communities that enable and promote healthy habits

Equity and local economy Be fair – support local businesses and affordable housing

Culture and community Boost community by creating shared spaces and develop a culture of sustainable living

Land and nature Create a connection with nature, and enable it to thrive

Sustainable water Use water-efficient appliances and increase resilience to flooding

Local and sustainable food Promote plant-based choices and provide space to grow food

Travel and transport Reduce the need to travel and make active travel the easiest option

Materials and products Reduce embodied carbon and source responsibly

Zero waste Think circular throughout design, construction, and operation

Zero carbon energy Design for net-zero carbon then make sure you achieve it

Our framework turns daunting sustainability challenges into achievable, collaborative steps

Find out more

Core to implementing One Planet Living is to establish the needs of a community against each of the One Planet Living principles, using all available data and existing research. Establishing a vision for a local area should be done in partnership with the community, to ensure that everyone’s perspectives are considered and that the goals are grounded in the lived experience of people’s day-to-day lives. This process will generate an action plan setting out outcomes, actions to achieve them, and indicators against which progress will be measured. Reporting publicly on your goals and actions creates transparency and accountability. And regularly reviewing your progress enables you to refresh your vision (stage 2) if necessary, and your action plan (stage 3). These should be considered ‘live’ documents and be constantly updated.

| Stage | Output | How |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Needs analysis | Evidence base | Desk-based research |

| 2. Visioning | Goals and ambition | Interactive workshops |

| 3. Action plan | Outcomes, actions, indicators | Collaborative planning |

| 4. Publicly report | Transparency and accountability | Communications, presentation |

| 5. Review | Learn and adapt | Objective analysis |

Following this method, local authorities have enabled new sustainable development by combining a holistic approach to sustainability with a ‘triple-bottom line’ perspective that considers the environmental and society benefits of new development, rather than prioritising short term financial returns.

BedZED

The multi-award-winning BedZED development was the UK’s first large-scale sustainable community when it was developed 20 years ago through a collaboration with Peabody Trust, Bill Dunster Architects, Arup, and Bioregional. Despite some teething trouble due to its experimental design, BedZED remains an internationally recognised flagship for sustainable development. The mixed community includes 100 homes, (50% of which are affordable) a specialist college and employment space, community facilities, an open playing field, green gym, meadows, and allotments.

BedZED residents enjoy a strong sense of community and benefit from low utility bills, using 27% less electricity and 36% gas than comparable households. BedZED homes sell at higher prices, and more quickly, than those in nearby streets.

The development was unlocked by London Borough of Sutton, which agreed to dispose of the land at a below-market rate by factoring the ‘abatement cost’ of the carbon emissions that it would save into the sales price

Sutton farm

Sutton Farm, established by Bioregional in 2010, but now independently owned and operated, represents another example of public assets being utilised for wider community benefit, transforming underutilised Surrey County Council-owned land into London’s most productive farm.

Sutton Farm was created after community consultation in the local area established a need for access to fresh fruit and vegetables, to improve health and reduce the carbon emissions associated with the transport of food.

Saxon Court

Bioregional is supporting mixed-use developer Socius on detailed designs for the redevelopment of Saxon Court, Milton Keynes’ first office block, following the granting of planning permission last year. As well as providing refurbished and extended office space, Saxon Court will include 288 new apartments for rent, and a public square for community events.

The site was released by Milton Keynes Development Partnership in a competitive OJEU tender process, granting Socius a 999-year investment lease, following a successful local campaign for the offices to be retained and redeveloped.

This was made possible by calculating the broader sustainability benefits of the scheme, which will generate £300m of social value over the next 20 years. The development will be fossil fuel-free, deliver a 25% net gain in biodiversity onsite, and will offer residents the use of a car-sharing club rather than private parking spaces.

Quantifying the social, economic, and environmental benefits of new development is not yet an exact science. Whole-life economics is difficult for practitioners to apply in a financial crisis, and there is the added political challenge to get buy-in to social value, but there are some key principles that estates professionals can follow.

- Think holistically. Examine a broad range of principles – societal, ecological, and economic – to understand how they interconnect, and how technological and demographic trends will influence people’s needs in years to come.

- Challenge short-term financial mindsets. Overcome short-termism by creating a local needs analysis that is evidence-based to justify decisions and non-financial options. When influencing others, learn to speak their language - be a chameleon. And remember that genuine personal conviction and passion can open doors.

- Collaborate in partnership. Find local champions and work with a range of partners. This will generate opportunities to leverage greater impact.

- Maintain an open mind. Being an agent of positive change is hard work, and it is easy to be a blocker by mistake, especially from a position of power.

- Act with urgency. It’s called an emergency for a reason, and what we do this decade will determine our future. The public desire and demand for sustainable credentials and activities is very high. However, awareness needs to cut through complexity of the issues to differentiate greenwash from real projects. We now need to focus on how we can create the business case for truly sustainable development that is fully integrated into our communities.

About Ronan

Ronan Leyden is Director of Consultancy at Bioregional, the award-winning social enterprise and sustainability consultancy. Bioregional works with partners across the built environment, supporting asset owners such as housing associations and real estate funds to revitalise legacy and heritage buildings; partnering with business improvement districts to create sustainable high streets and leisure destinations; and with local authorities to create local planning policies that support the UK’s transition to net zero.

Get in touch with Ronan below if you'd like to learn more about how we could help your project or organisation.